Underground fortifications and shelters in Rijeka and its surroundings

The city of Rijeka lies at the mouth of the Rječina river, at the foot of a mountain barrier which is the narrowest (40 to 50 km) and the lowest (Gornje Jelenje, 929 m; Postojna Gate, 698 m) in its hinterland. Rijeka has developed in a location where the Adriatic Sea cuts deep into the European mainland, which made the shortest sea connection between the countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the overseas countries possible.

Historical circumstances leading to the formation of underground fortifications and shelters

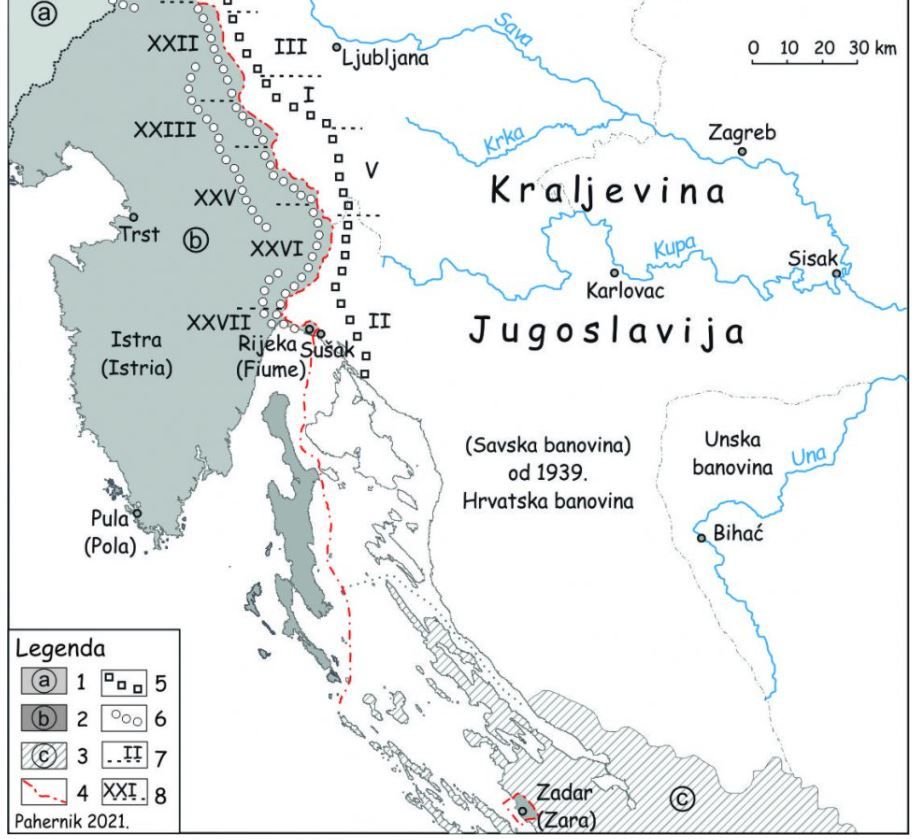

Due to its geographical position, Rijeka has been of exceptional geostrategic importance all throughout history. In the first half of the 20th century, the Kingdom of Italy expressed territorial claims to the eastern Adriatic coast towards the Austria-Hungary, and, after the end of World War I, towards the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia).

The Kingdom of Italy left the Triple Alliance in 1914 and in April 1915 secretly signed an agreement known as the Treaty of London with Entente, which promised it parts of the Croatian Adriatic coast. In return, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary. After the war, Austria-Hungary disintegrated, and Italy gained part of the promised territory. Finally, the Treaty of Rapallo determined the border between the Kingdom of SCS (later Yugoslavia) and the Kingdom of Italy, according to which the city of Rijeka belonged to the Kingdom of Italy.

Italian Vallo Alpino (Alpine rampart)

In the 1930s, the Kingdom of Italy began the construction of the Alpine rampart (Vallo Alpino), a complex system of fortifications for the protection of the Italian border. The part towards Yugoslavia is called Vallo Alpino Orientale (about 220 km long).

The fortifications were adjusted the morphology of the terrain, and since the terrain is hilly and mountainous, the fortifications were dug into the rock mass wherever the terrain made it possible.

General description of the Alpine rampart fortification:

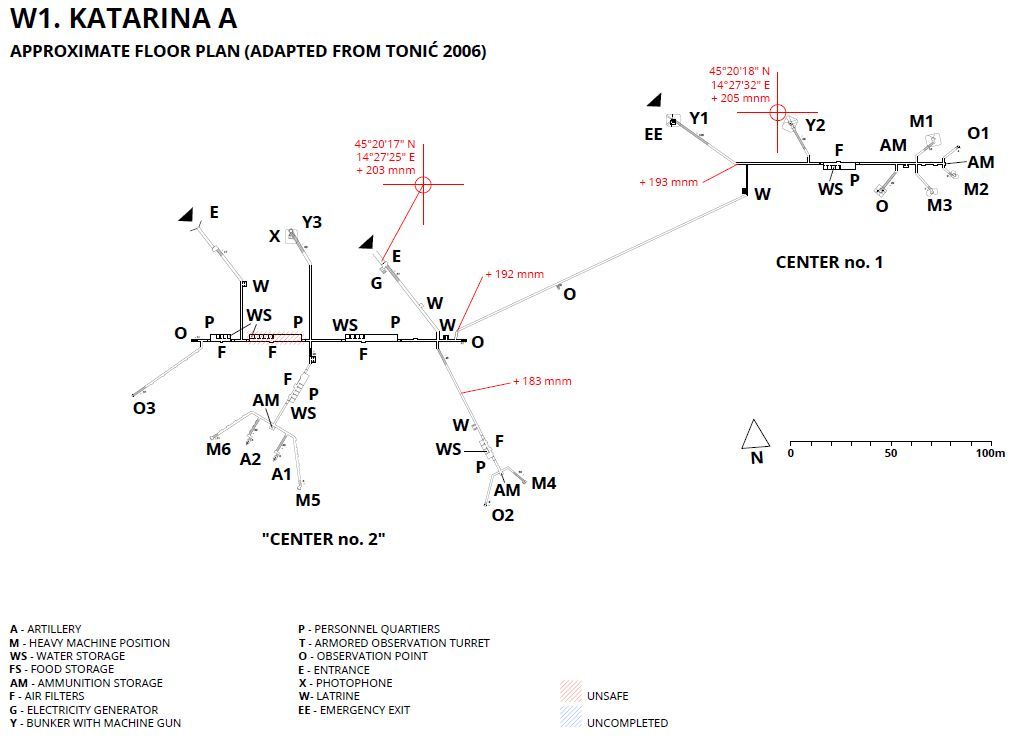

“The entrance to the fortification was usually built as a well-masked concrete structure within some natural depression in the terrain, facing away from the enemy side, and usually defended by a loophole within the block itself, in a door, or further down inside the corridor. Depending on the terrain profile at the location of the fortification, the garrison shelter was reached either by a corridor leading horizontally inward or by a staircase leading down to the level of the shelter, which was entered through a pair of gas-tight doors of the same type as the doors on submarines. The underground rooms for the garrison were built as corridor extensions, with a volume of up to over 200 cubic meters. Clean air for the weapons handlers was provided by a special pipeline system with connections for the gas masks of the soldiers. Apart from the main entrance, the fortifications usually had a separate security exit.”

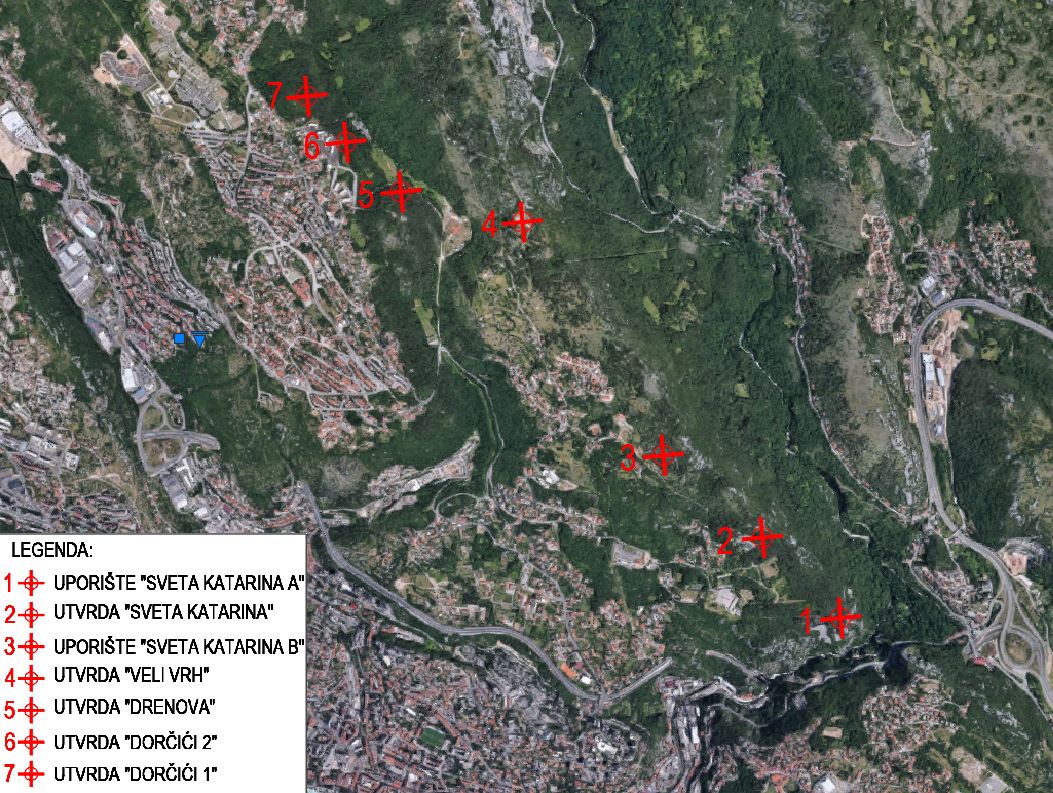

Significant positions of the Alpine ramparts in Rijeka are shown below:

The most important buildings that stand out from the rest with their size are the strongholds of “Sv. Katarina A” and “Sv Katarina B”, built from 1931 to 1941. The plan of the stronghold “Sv. Katarina A” is shown below.

There are also numerous shelters in Rijeka itself. Recently, a tunnel with an entrance next to the Cathedral of St. Vitus and running below Rijeka’s Old Town to the yard of the Dolac Elementary School was opened to the public. It is 330 m long and was dug in the rock mass by the Italian army from 1939 to 1942 for the protection of the civilian population from aerial bombardment. In some places, the tunnel runs at a depth of ten meters. It is about 4.0 m wide and 2.5 m high on average.

The entrance to the shelter is visible in Žrtava fašizma street, not far from the Governor’s Palace (shown in the photo below).

Rupnik line

Across from the Italian side, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia began constructing the Rupnik line divided into six sectors, with Sector II being constructed in the hinterland from Rijeka (Figure 1). General Leon Rupnik was appointed commander of construction.

“Due to financial difficulties, lack of time and the German occupation of the Czech Republic, from where part of the steel for construction and a good part of weapons were imported, construction plans were changed significantly. The construction of large underground fortifications, i.e., heavy facilities, was halted, and the construction of small bunkers and other light facilities continued.” [3]

“The so-called “mulatjera” (bridle path), a well-built road, led to each of the bunkers, and was used to deliver materials during construction, and later as the basis of logistical support to the bunker. The entrance to the bunker was closed by a metal lattice door. These were followed by a small L-shaped corridor at the end of which the real metal door of the bunker entrance stood.” [3]

Conclusion

The consequences of a turbulent past and the geostrategic position of Rijeka are seen in the remains of numerous underground fortifications and shelters. A favorable factor of their construction was the excavation in rock mass, which provided the necessary protection against attacks.

The most important buildings were constructed in the scope of the Italian Alpine rampart (Vallo Alpino). On the other hand, smaller fortifications were built in the form of small bunkers and other light structures in the scope of the Yugoslav Rupnik line.

The city of Rijeka and its surroundings host a significant number of abandoned military fortifications that can be used for tourism and culture purposes.

*References:

[1] Dokumenti (1915-1955) za istraživanje jugoslavensko-talijanskih odnosa, 1975, Časopis za suvremenu povijest, Vol. 7 No. 1, 1975.

[2] Vladimir Tonić: Tragom Alpskog bedema u Rijeci i Hrvatskoj, Udruga Slobodna Država Rijeka, 2011.

[3] Mladen Pahernik: Fortifikacijska linija “Zapadnog fronta” Kraljevine Jugoslavije, Hrvatsko geografsko društvo, 2021.

[4] https://www.projectrevival.eu/en/object/fortification-sv-katarina-a/27